A Guide to the History of Meth

By the time the TV show Breaking Bad broadcast its final episode in 2013, it had already been hailed as one of the greatest TV series of all time. The show was praised for its depiction of the methamphetamine industry as entertainment; but behind the storytelling and the awards, Breaking Bad was another chapter in the long history of meth in America, one that is still being written long after the closing credits.

The Roots of the Ephedra Plant

Methamphetamine originated in very different settings than the southwestern United States. The drug was first developed as a synthesized alternative to the ephedra plant, a type of shrub that has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for over 5,000 years. Its extract was used in the treatment of asthma, hay fever, and bronchitis as well as other conditions that affect breathing like the flu or allergies.

In 1885, a Japanese chemist named Nagai Nagayoshi isolated the active chemical in ephedra, as part of his research into using Western science to better understand Eastern medicine. Based in Berlin, Nagayoshi discovered that ephedra’s active chemical was a stimulant, which became known as ephedrine. His work came at a time when cocaine was enjoying worldwide popularity for its use as a wonder drug, and all eyes in the scientific community were on the lookout for the next big thing. Nagayoshi isolated a stimulant that made people feel more alert and awake, but the real breakthrough came in 1919. Akira Ogata, also living in Berlin, used phosphorus and iodine to break ephedrine down to a crystalline form. In doing so, Ogata created the first crystal meth in the world.

The Benzedrine Craze

In the United States, the first exposure to meth came through the marketing of amphetamine in an inhaler for the treatment of asthma and nasal congestion in 1932. So innocuous was the concept of using amphetamines medicinally that the medication (known as Benzedrine) was available without a prescription. Soon, wrote The Atlantic, enough people had discovered that the amphetamine in the inhalers made them feel energized, alert, and really good about themselves. Until the 1950s, amphetamines became a drug of choice for artists and scientists to burn the midnight oil and boost their creativity, not dissimilar to the way the world had flirted with cocaine as a mainstream indulgence.

The Benzedrine craze quickly spread, and pharmaceutical companies started marketing amphetamine pills for narcolepsy. In 1935, a physician in Los Angeles conducted one of the first scientific studies on the effects of amphetamines and noted that people who took the drug felt strongly euphoric and exhilarated as well as a “lessened fatigue in reaction to work.”

By this point, adverse reactions to amphetamines had not been documented. On the other hand, the reaction of users not feeling tired at all was very well noted, especially by various militaries around the world. When World War II broke out in 1939, it mobilized armies on a scale never before seen in human history. In Germany, the Temmler pharmaceutical company sold methamphetamine tablets under the brand name Pervitim. Der Spiegel writes of how the product was marketed to soldiers as an “alertness aid” to “maintain wakefulness,” even while warning users not to take too much at a single time. But as the war dragged on, soldiers began to request more and more Pervitin, finding that it not only helped them stay awake, but it helped them cope with the struggles of military life in Nazi Germany.

Keeping an Army Awake

Like in the United States, methamphetamine was in use before Germany went to war. It first came to popular attention in 1938 when an important physiologist in the German Army guessed that methamphetamine “could keep tired pilots alert and an entire army euphoric.” Der Spiegel says that meth was thought of as the perfect war drug for a country that was being militarized. In September 1939, the same year Germany invaded Poland, meth was tested on university students who became instantly and impressively productive despite being sleep-deprived.

From that moment, the German Army made it official policy to distribute millions of Pervitin to soldiers on the frontlines who dubbed it “tank chocolate.” The news spread across the English Channel where British newspapers reported that the German soldiers threatening Europe were using a “miracle pill.” Before France surrendered, the German Wehrmacht had been issued 35 million tablets of methamphetamine with even one of Germany’s highest-ranking soldiers consuming Pervitin on a daily basis. Even when it became clear that methamphetamine was ruining soldiers’ lives, the army continued to issue the drug to its troops. British soldiers, as well as American soldiers stationed in Britain, got in on the methamphetamine habit to keep up with their German counterparts.

In Japan, the drug was used to chilling effect. By October 1944, the war had swung against the Axis powers, and the Empire of Japan, desperate to regain momentum and avenge the humiliation of military defeats, charged special units of pilots as well as its marine and land troops to carry out suicide attacks on the American forces in the Pacific Theater. To do this, these pilots were given methamphetamine (called “philopon,” which roughly translates to “love for work”) in high doses and then ordered to use their planes as guided explosive missiles to destroy American warships. In the same way British soldiers heard about the miracle pill that their German combatants were taking, the reality of Japanese kamikaze pilots (fueled by methamphetamine) became one of the legends of World War II.

Methamphetamine ‘could keep tired pilots alert and an entire army euphoric.’

Call Now (619) 577-4483

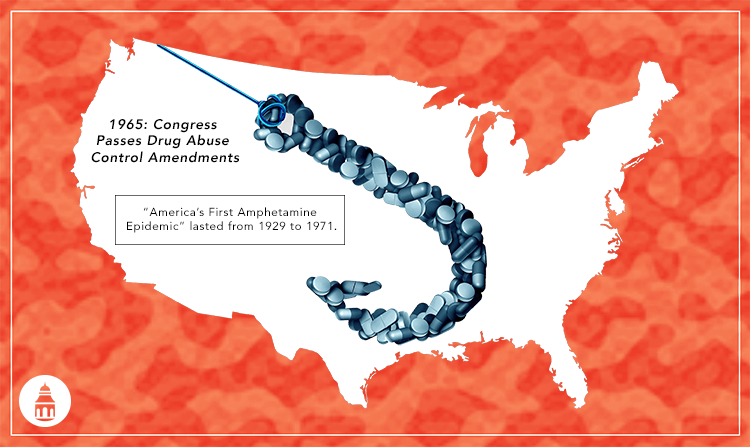

America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic

After the war ended, the United States experienced an economic and cultural boom, and the drugs that fueled German and Japanese soldiers were enjoyed by writers for their stimulant and creative properties. Beat Generation writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs drastically and vividly increased their literary output by hitting their Benzedrine inhalers every day, only relenting after the physical and psychological effects of chronic methamphetamine exposure became too much to bear.

The shift marked the end of America’s infatuation with amphetamines, as more and more Benzedrine users complained of the health problems they experienced: everything from rapid heart rate and psychotic episodes to digestive problems and an inability to stop using Benzedrine. This led to what the American Journal of Public Health to write that “America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic” lasted from 1929 to 1971. Even after the Food and Drug Administration ordered that Benzedrine products would require a prescription, abuse of the substance continued. The journal notes that in the early 1960s, amphetamines were still thought of as “innocuous medications,” with family doctors prescribing them to housewives to help with the daily duties and banalities of housework. Even President John F. Kennedy received regular injections of 15 mg of methamphetamine, in part to cope with the pain of lingering war injuries but also to help maintain the image of a young and charismatic leader.

For the rest of the decade, amphetamines were regularly prescribed as a weight loss aid, and healthcare professionals made a killing. One diet doctor paid just $71 for 10,000 amphetamine pills and sold them for $12,000. It was estimated that at the height of the craze, a total of 2 billion amphetamine-based weight loss pills were consumed. The FDA estimated that of as many as 10 billion 10 mg amphetamine tablets manufactured in a single year, almost 50 percent of them were “diverted” – that is, they were used for recreational or unofficial purposes.

Throughout the 1960s, Congress discussed ways to control the unlawful and dangerous diversion of amphetamines. In 1965, they passed the Drug Abuse Control Amendments with the idea of limiting the manufacture of amphetamines as well as other risky substances. However, despite the implementation of the legislation, there was no sign that consumption of amphetamines reduced.

8 Billion Amphetamines

The debate and concern about amphetamines became part of the political conversation on drug abuse in general into the 1970s. A year after Congress convened a hearing on the topic of crime in America related to 8 billion amphetamines, President Richard Nixon signed the 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, which established the set of “schedules” for controlled substances that the Drug Enforcement Administration uses today. But the pharmaceutical industry had enough influence to ensure that only a small amount of rarely used methamphetamine products were placed in Schedule II where they would receive tight regulation and enforcement; oral amphetamine, on the other hand, was placed in Schedule III, where it would be free of manufacturing quotas, enjoy less strict recordkeeping, and prescriptions could be refilled up to five times. Unsurprisingly, this did little to curb amphetamine consumption; between 1969 and 1970, reported legal production of amphetamines dropped only 17 percent.

The government moved quickly. In 1971, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (which would go on to become the modern-day Drug Enforcement Administration) used its administrative authority to shift all amphetamine-related products to Schedule II, including popular medications like Ritalin and Preludin (a diet drug), both of which were being used off-label and recreationally. Schedule II drugs require a new prescription for every refill, and doctors and pharmacists were at risk of prosecution if they did not keep records.

The intervention of the narcotics bureau was immediately effective. Prescription sales of amphetamines and similar drugs dropped by 60 percent below their usual level after the new restrictions were made official, as many patients and their doctors accepted that the off-label use of amphetamines would be made illegal at the highest level.

Putting amphetamines in Schedule II gave federal drug enforcement authorities and the Food and Drug Administration the power to limit their production to quantities required by medical standards and no more. While this was happening, the FDA was tightening the scope of legitimate amphetamine use, declaring that the drug was not conclusively proven to effectively treat obesity and depression. Only narcolepsy and attention deficit disorder were approved for treatment with amphetamine-based medications.

The turning point came in 1980 when the DEA put amphetamine’s key chemical component, Phenyl-2-propanone, into its Schedule II list of controlled substances. The component, also known as P2P, had been used by motorcycle gangs in their meth production efforts, diverting the chemical from its original intent as a swimming pool cleaner.

Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine

With the regulation of P2P, the illegal production of amphetamine took a temporary hit, but the underground drug manufacturers were not deterred. They turned to ephedrine – the active chemical compound in the ephedra plant and an ingredient found in basic over-the-counter cold and allergy medications – and used it to make methamphetamine. While cocaine and heroin required some expertise in its production, what fueled the second amphetamine epidemic is that methamphetamine is “simple and quick” to make. The ingredients can be legally purchased from a hardware store and a pharmacy and put together in anything from a basement to a houseboat (or a recreational vehicle, as depicted in five years of Breaking Bad).

Methamphetamine is twice as potent as amphetamine, warns PBS, and led to a wave of crime, visits to emergency rooms, and drug-fueled cases of child abuse and neglect. Additionally, meth is so much easier to produce that the FDA eventually had to respond by moving pseudoephedrine-based cold remedies, like Sudafed, to behind the counter at pharmacies. Some states require a doctor’s prescription for patients to receive pseudoephedrine products for fear that the chemicals can be diverted to meth labs.

Methamphetamine is twice as potent as amphetamine, warns PBS.

It’s Never Too Late to Get Help

The Cartel Connection

The use of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine to make methamphetamine, or crystal meth, resulted in a dramatic spike of abuse in the early 1990s. In the decade between 1994 and 2004, the use of meth rose from just under 2 percent of the American population to approximately 9 percent.

Meth became such a commodity on the black market that some Mexican cartels even switched from their traditional cocaine business to meth. For example, Luis and Jesus Amezcua Contreras, two Mexican brothers who led the Colima Cartel, sourced out a factory in India to produce ephedrine that would be brought into the United States via Mexico. In 1994, a US Customs agent accidentally discovered 3.4 metric tons of ephedrine powder on a cargo plane doing a delivery from Switzerland to Mexico, and the DEA traced the shipment back to the Contreras’ factory. It transpired that in the single span of 18 months, the brothers smuggled 170 tons of ephedrine into the United States, which could have been used to make 2 billion hits worth of methamphetamine.

As a result of the bust, the US government asked foreign manufacturers to tighten their ephedrine production regulations. This was successful. With cartels struggling to secure ephedrine shipments, the chemical purity of meth in America suffered. The Contreras brothers were arrested in 1998, by which point they were responsible for as much as 80 percent of the methamphetamines being distributed in America. The Colima Cartel (now operating as a branch of the infamous Sinaloa Cartel) is still in the business of pseudoephedrine smuggling and diversion, as are many other organized crime rings in Mexico.

The DEA vs. the Pharmaceutical Lobby

In 1986, Gene Haislip, the head of the Office of Diversion Control at the DEA, put together legislation that would have made companies making 14 of the chemicals used in the production of illicit drugs, including ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, track their sales and imports. Had the legislation passed, it is possible that the meth manufacturers of the future would not have been able to so easily divert pseudoephedrine as a precursor, but Haislip’s efforts were blunted by the pharmaceutical industry, which argued that “the DEA was confused about who was the bad guy,” in the words of a former lobbyist for the industry. Drug corporations made the case that DEA legislation would have unfairly targeted consumers, depriving them of the medications they needed for even simple ailments.

Before his death, Haislip told PBS that the pharmaceutical industry had considerable influence in Washington, DC, and their focus on making money and selling products clashed with the efforts of law enforcement; one side looked at chemicals as commodities to be protected, and the other thought of them as harmful agents to be controlled. According to The Fix, the market for cold medicines was worth $3 billion during the 1980s. While Haislip was instrumental in getting Quaaludes banned (which, after years of bad press, the drug lobby had no interest in protecting), he could not shake the vested interests of the pharmaceutical lobby. To this day, pseudoephedrine are not federally regulated, and in the states that do not require prescriptions for such products, the argument is the same.

The reality of trying to clamp down on methamphetamine production is that for every legislative effort that has been put forward, the underground laboratories simply go deeper in their attempts to stay ahead of enforcement.

For example, when the FDA mandated that pseudoephedrine manufacturers register with the DEA, drug rings created dozens upon dozens of scam operations with the sole idea of swamping the DEA’s processing and allowing a small number of corrupt manufacturers to sneak through obscure and technical loopholes. Unable to process a mass of applications for pseudoephedrine, the DEA was forced to grant temporary licenses, which allowed meth operations to continue to import and divert pseudoephedrine. When the DEA would finally catch up to one ring, there was always another to take its place.

Pseudoephedrine from Canada

The southern border wasn’t the only problem for America’s drug enforcement. With every DEA crackdown, meth cooks in the Central Valley got desperate that they would run out of pseudoephedrine to keep their production going. They turned to Canada where the precursor was unregulated. Between 1999 and 2003, Canada’s bulk pseudoephedrine imports for the manufacturing of cold medication pills increased four times over. The North American partners worked together to close the route with Health Canada adopting a similar regulation system to its American counterpart in order to cut off the import of pseudoephedrine to American meth labs.

In 2002, The New York Times wrote that Canada had become “the leading supply route for [pseudoephedrine] to the United States.”

The DEA teamed up with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Drugs and Organized Crime unit in 2003 and made arrests across 10 Canadian cities; three Canadian chemical companies were hit with federal charges for illegal drug manufacturing and trafficking. The Oregonian explained how the RCMP would track pseudoephedrine smuggling from Ontario to the American border crossing at Detroit and then hand their evidence over to the DEA at the checkpoint. The DEA would follow the trail, which inevitably led to California and the meth labs waiting to receive the shipments.

The cooperation was successful in its mission. Meth labs across California were either busted by the DEA or shut down out of fear of being caught, but the corruption in Mexico allowed for the opening of more labs to account for the fallout. Notwithstanding all the efforts of law enforcement, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported in 2003 that 12 million Americans over the age of 12 had tried meth at least once.

Call Now (619) 577-4483

Tightening Pseudoephedrine Access

In 2004, Mexico imported 224 tons of pseudoephedrine, estimated to be twice the amount needed to make cold medicine. Inevitably, the precursor was cooked into methamphetamine, then smuggled across the border into the United States. The result, says PBS, is that the chemical purity of meth on American streets is higher than it had ever been. In April of that year, Oklahoma responded by becoming the first state to pass a law that restricted pharmacy sales on pseudoephedrine by requiring retailers to move their pseudoephedrine-based cough products behind the counter; in order to make a purchase, customers would have to show identification and sign a register. A 2012 update to the bill was called “the toughest in the nation” by local lawmakers and put forth over the objections of the pharmaceutical lobby as well as physicians and pharmacists themselves who raised concerns that the steps might dissuade people from buying legitimate cough remedies even if they had no interest in diverting the product for meth production. For law enforcement in Oklahoma, the problem was simpler: The previous year, police had broken up 843 meth labs, 429 of which were in the city of Tulsa alone, and all of which used pseudoephedrine for its easy availability and low price.

Combatting an Epidemic

In 2006, Congress passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act, which, while stopping short of full regulation of precursor chemicals, imposed strict nationwide limits on how over-the-counter cold medicines can be sold in pharmacies. Specifically, remedies with pseudoephedrine had to be moved to behind the counter, sales had to be tracked, and more than 7.5 grams could not be sold to the same customer in a 30-day period. While the law had the immediate effect of making life impossible for homegrown meth labs (including a drop in the rates of treatment admissions for methamphetamine abuse), the vacancy was quickly filled by the Mexican cartels who pushed their American competition out of the market once and for all.

The Washington Post noted that drug rings based south of the border had been using “super labs” (facilities that produce meth on an industrial scale) to pump out the drugs and ship them across the southern border. Notwithstanding the effectiveness of the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act, Mexico’s lax regulations and laws, as well as corruption in the state and federal police forces, allow the cartels to easily bring precursor chemicals into territories they control. Super labs have become so effective in churning out meth that in 2016, Nigeria’s National Drug Law Enforcement Agency dismantled a super lab in Asaba Delta, which was capable of producing four tons of crystal meth on a weekly basis with the idea of selling the product across Asia. Nigerian authorities arrested four Mexican nationals as part of their operation and confirmed that the lab was built “with Mexican expertise.”

The Failing Fight against Meth

In an acknowledgement of their role in the problem, the Mexican government at first restricted the sale of pseudoephedrine to fulltime pharmacies in 2006, dropping the number of retail outlets that sold the precursor from 51,000 to 17,000, and then banned the import of pseudoephedrine completely in 2009. PBS notes that this again affected the chemical purity of crystal meth in the US, even as the United Nations called meth “the most abused hard drug on earth” in its World Drug Report. In 2006, there were an estimated 26 million people around the world addicted to methamphetamines, which equaled the combined number of heroin and cocaine users at the time. Over 1 million such users lived in America alone.

The combined multinational efforts of law enforcement and governmental bodies have helped slow the pace of methamphetamine trafficking, but the problem is still a large one. Deprived of easy access to pseudoephedrine, cartels have focused their efforts on underground labs in California, making the state produce more meth than the next five biggest producing states combined. Meth is “flooding” California thanks to the cartels, and as recently as 2015, seizures of crystal meth at US ports of entry on the California-Mexico border broke records: 14,732 pounds of the drug, accounting for 63 percent of all synthetic drug seizures across the country.

The Washington Post writes that so much methamphetamine has entered the US that the surplus has trickled back into Mexico itself.

The trade is again controlled by the cartels who can operate with much more freedom and violence in their native land than they can in the United States. Many Mexicans use methamphetamine as an escape from the bloodshed and poverty that their country has become known for; others use it because it is so widely available. While the standoff develops between the government and the pharmaceutical lobby in the US, a researcher at the US-Mexico Border Health Commission told the Post that Mexico is “failing in this fight against addiction,” adding another tragic chapter to the long history of meth.

It’s Never Too Late to Get Help